Selection Philosophy

There had been many initial candidates from within Finning in the UK and Canada, most of whom were field service engineers and workshop personnel. By the time we left for Sweden these had been shortlisted to five mechanics: two Canadian and three British.

These had been chosen from a much bigger list after they had each proved their technical ability to specialist trainers at Finning, and survived interviews by Sir Ranulph and his ‘black talk’ (a no-holds-barred description of the reality that lay ahead). The five had been ranked in terms of their technical ability, and this information was passed on to the selection team.

It is important to stress at this early stage that whilst we were looking for the ‘best’ candidates, this didn’t necessarily mean those with the most amazing backgrounds, advanced skills in underwater knife-fighting and crocodile wrestling. Our prime candidate was someone who was not only competent, but also compatible with the existing team members. During the traverse, the team will be living in extremely confined quarters with no one else but their fellow team members for company for hundreds of miles in any direction, through the darkness of the Antarctic winter. People with big personality swings, for example, would be a disastrous addition; those who can’t keep on top of the personal administration and leave a trail of discarded equipment all around the living and science caboose will soon become tiresome.

Another thing we’d be looking for was how people changed when they got cumulative tiredness and were then presented with an unwelcome task. Did they rise to the occasion or did they get moody, sullen or aggressive? We needed someone who was thorough and could be relied on to complete a task; someone who, if they didn’t know something, had the humility to say so rather than muddle through and possibly make a bad situation worse.

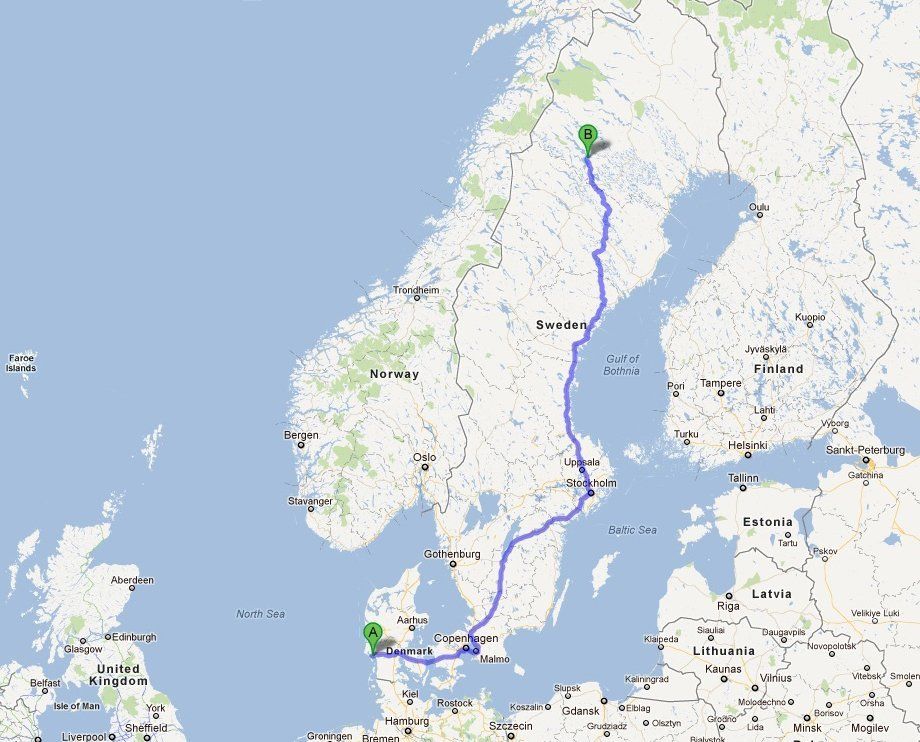

These are all intangible personality facets, not picked up from a CV or even an interview. The field testing in Sweden allowed us to have prolonged exposure to our shortlisted candidates, in a regime that we could control to bring out the traits we were looking for. However, the selection process got underway even before we arrived in Sweden, as the candidates’ competencies for logistics and navigation were put to the test during the long drive and ferry crossing from England.

Part 1: Cannock to Esbjerg

All of the equipment and tools needed to service the D6N were packed into a dedicated Finning service van, with all the equipment for testing filling another entire panel van and much of our own minibus besides. This meant we now had a three-vehicle convoy – rather than the single van we originally anticipated – and so we were grateful that DFDS, the ferry company, extended their sponsorship to include all three vehicles.

Who was there?

Panel Van: Expedition co-leaders Sir Ranulph Fiennes and Anton Bowring travelled together alone, allowing them a rare uninterrupted opportunity to plan for the greater undertakings to come. The length of journey would mean that Anton would have to, at some stage, let Ran drive. This is not for the feint hearted, but at least he would be restricted to the speed of the convoy.

Finning Service Van: Candidate mechanics Craig Lusada and Andrew Varley, from Yorkshire and project design engineer Andy Thomas, who had been slaving away for months designing the modifications to the D6N bulldozers.

The Minibus: Canadian candidates Matt Stevely and Spencer Smirl, were joined by the UK’s Danny Main, as well as Steve Holland, Russell ‘Tomo’ Thompson and Geoff Long.

Whilst Danny underwent a last-minute minibus training course, the task of planning the route with potential fuel and food stops was undertaken by Craig and Andrew, which they did with meticulous detail. Walkie-talkies between the vehicles would keep us in touch, although watching a Canadian trying to understand a Yorkshireman over the radio proved to be an ongoing source of entertainment.

The expedition at this point was without most of its ‘final’ team members, so the selection team underwent additional training to allow them to field test some of the equipment. Steve would do his best with the Iridium satellite communication system and the ground penetrating radar; while Geoff and Tomo both underwent film training with BBC News and Panasonic so that they could document the trip until a BBC News team joined later on. The Coldest Journey will be self-filming, so this trip also served as a useful measure of how quickly the skills could be consolidated.

Despite the fact that the top speed for the minibus was restricted to just 62mph, we got to the DFDS check-in at Harwich in plenty of time. Geoff and Tomo disappeared to plan the filming sequence of our vehicles boarding the ferry. To prevent our artistic requirements from mucking the boarding procedure we were allowed to board last. Thankfully there wasn’t too much traffic – the North Sea in January is not a tourist hotspot.

Once in the cavernous vehicle deck of the vessel we heard a Danish voice over the tannoy: “Would a Mr Ron Feens (sic) please come to the information desk”. We all dutifully followed with our personal gear, the broadcast cameras and other paraphernalia to find out that we had been upgraded to ‘Commodore’ class. It would seem that travelling with this Ron Feens bloke had its perks!

It was our intention that the candidates didn’t have too much downtime and so straight after dinner we set up a projector for a series of presentations. First off Steve Holland delivered a powerpoint prepared by Dr Mike Stroud on the hazards of working in the cold, possible injuries and how to avoid them.

With health and safety duty fulfilled we then put on the film that was produced after the Transglobe Expedition undertaken between 1979 and 1982. This was the first and only circumnavigation of the world by its polar axis, and the film served as a very useful reminder to all, just what the team had achieved back then and that the public image of Sir Ranulph, now as the eccentric pensioner is far removed from the truth.

Suitably chastened by the exploits of the Transglobe team and just when they thought they were free to get some sleep, the candidates were presented with blank sheets of paper and asked to write an essay entitled “What is the point of exploration in the modern World?” whilst the selection team then retired to discuss their first impressions of the candidates.

After a comfortable night in Commodore class followed by a hearty breakfast, the team assembled for a series of sessions run by Tomo. As part of his day job he runs a lot of corporate team building and development exercises which he adapted to see how our candidates interacted with each other and dealt with specific challenges.

Part 2: Esbjerg to Arjeplog

Esbjerg to Arjeplog is just over 1,200 miles, a journey we started at lunchtime on the Monday. We had chosen to do the drive in one hit partly to save on the cost of hotels but mostly to give our mechanic/driver candidates their first sustained task. Every few hours they would rotate between driving, resting and navigating, changing at fuel or food stops. After a while the job of the navigator is less map reading and more to make sure the driver stays awake. The house rule in the Transit minibus was that the driver got to choose the music.

It didn’t take long for us to realise that those travelling ‘Transit Class’ had the better deal. We generally had more room to stretch out and where the seats had been removed at the back, to stack equipment, there was a level and quite comfortable sleeping platform. We also had a couple of portable DVD players – life was good. These luxuries did not exist in the Finning Service van or Anton’s panel van.

Having the three candidates rotate the driving allowed the selection team to observe how they interacted, what they had to talk to about, the views on a wide range of subjects, not forgetting their driving ability and mechanical sympathy. Andy Thomas of Finning was with the other two candidates in the Service van and we would chat at fuel stops to get a measure of how they were fairing. Interestingly, offers by us to swap personnel amongst the vehicles were turned down, each sub group quickly developing its own identity.

It is always to interesting to see how when Ran is ‘in the field’, temporarily removed from the strategic tasks of the expedition such as dealing with sponsorship and permits, he comes alive and is far more relaxed.

The drive through the night was a long one and for almost all of the stops for fuel and food, the diet was MacDonalds. This is OK, but for breakfast, lunch and dinner it doesn’t take long to go through the menu. The ‘golden arches’ have done very well in Sweden.

In the North of Sweden, with occasional glimpses of the Baltic, the countryside was whiter, colder and the roads much quieter. This was an opportunity to film scenic footage. There was much leapfrogging of vehicles dropping off Geoff with his camera, with Steve and Tomo to act as spotters and on the radio to the convoy hiding around the nearest bend. This filming provided welcome breaks from the driving and a bit of fresh air. The artistic reservoirs however were soon exhausted – we tried the camera, high, low, wide shots, tight shots, static, panning and everything else we could think of that would meet the demands of Mark Georgiou of the BBC. The locals were then treated to Geoff hanging a very expensive Panasonic camera out of different windows of the moving van to get actions shots (and cold hands).

Later in the day we got our first moose warning road signs. These and reindeer are a major traffic hazard in this part of the world. They are wonderfully adapted for ending up through your windscreen and are very solid, heavy beasts. They also seem to find roads fascinating. It is for their benefit that most of the trucks in the north have enough lights to make Blackpool seem dull. This light-fest is not much fun if you are driving the other way, completely blinded as they pass and then dealing with a cloud of spindrift snow.

The afternoon of Tuesday 31st January and after two days of non-stop travelling we pulled into the Colmis vehicle test facility on the outskirts of Arjeplog – consider it to be ‘Millbrook on ice’. With our documentary making heads on, we didn’t just all head into the reception, but checked that we could film in there and positioned Geoff to capture the process. There was much repeating of signing in by the same people from different angles and amounts of zoom. The poor girl on reception had probably had quite a normal day up until then.

At reception we were joined by Heinrich Huchtkoetter and Ricardo Weber from GKN Driveline. Heinrich had been our link with Colmis and handled all the local arrangements. It was through his efforts that we had a test track built to our unusual requirements. GKN Driveline work for all the major vehicle companies and come to Colmis each year to test new systems both on the frozen lake and the specialist landside track facilities.

Our first meal was in the simple dining room of the Simloc Hotel in the centre of Arjeplog. The menu was bread cheese and Elk Soup, a first for many of us. Once fed and watered, Ricardo from GKN led the convoy to our accommodation. This was a local house, which like many in the area is rented out during the depths of winter to the visiting car test engineers. No one knew the Swedish for ‘compact and bijou’ but it was apt here and we had a lot of people to cram in,with more due later.

The D6N Caterpillar we were to use for our test programme had arrived from Cannock ahead of us. This vehicle was one of the two that would go to Antarctica and it had been fitted with some, but not all of the intended modifications. The tests in Sweden would provide the confidence to push ahead with the final changes to this vehicle and to start the other one back at the Finning facility in Cannock.

Somewhere on its travels the D6N had been removed from the vehicle on which it left Cannock and put onto the trailer of another truck. On the bed of the truck itself, was the Lehmann sled that was also a key part of the test programme. Whilst it was great to see them both here together we now had a problem.

The loading ramps of the trailer were nowhere near robust enough for unloading the 18 tonne D6N. The truck driver pointed out a fixed loading ramp that he could back up to. The site owners looked at the modified, aggressive tracks of the D6N. Designed to bite into Antarctic glacier they would destroy this ramp and so we couldn’t use it.

We now had a functioning vehicle but our test track was over the hill. There was obviously no point in reloading onto the truck and because of the vehicle’s track design we couldn’t drive out onto the main road without ripping that up. The remaining option was a stint of cross country driving and trying not to take out more trees than strictly necessary.

The line of least resistance was investigated on foot and a plan put together so that the excursion could be filmed and photographed from safe vantage points. With everyone in position we were off. Some existing tracks were used for the first few hundred metres and then the vehicle headed off over the brow of the hill. The damage was limited to a few saplings.

A whole day had been spent unloading the vehicle, fitting its blade and moving it to the track. None of this counted as part of the formal testing but was an excellent illustration of how things will be away from the normal world – and at the moment it was still relatively warm.

From the candidate selection perspective, this series of delays and obstacles was very useful. Seeing how the individuals responded to events, who put themselves forward with ideas and who stayed in the background was all very telling.

We were now ready to actually start vehicle testing…

Part 3: Testing Time

Having got the CAT D6N and the ballasted trailer onto the test track we were at last ready to focus on our intended test programme. At this point we were joined by Mike Stroud and the BBC news team that consisted of Matthew Price with Julie Ritson on camera and Producer Mark Georgiou. The BBC were given the upstairs ‘Penthouse Suite’ of our shared house with Mike Joining Ran and Anton in the basement. With the addition of the Caterpillar PR filming and Geoff Long on the expedition’s own camera we had every angle covered.

The test track was compacted snow on underlying sand. We were unsure how the aggressive track pattern on the CAT would break this up. Concerned that we might only have one real chance to film the moving vehicle on a surface that looked right we carefully positioned the cameras for movement of the CAT and Lehmann sled. As it actually moved off we had reached a milestone in the programme. Thankfully the vehicle did not leave a trail of destruction making future filming much easier.

With CAT and trailer working well together we then introduced Ran, Mike, a pulk-sled and the Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) into the mix. This ‘Crevasse Detection Team’ moving in front of the vehicles would act as an early warning, hopefully far enough ahead that the direction of the vehicles could be changed to take a safer route. This test would give us a practical indication of what length of cable could be used to connect the GPR back to the vehicle. The display screen would be in the cab and the driver would make the call to Ran on what was being observed.

We had noticed during the day that the temperature was definitely on the way down. For loading and travelling purposes the CAT had some normal diesel on board with additive that would make it good to -28C. We also knew that the ‘local brew’ of fuel would work well for top ups. The Finning team had also brought a selection of spare filters and other components. Practise on changing these would help develop cold weather procedures. The temperature soon sunk past -28C and was well into the -30s by the time it got dark. We managed to film some of the sequences shown on the BBC News before the fuel in the CAT really started struggling. This had a major impact on our tests – we wanted to do some extended fuel burn runs at night when it was coldest but this swing from almost too warm to very cold caught out the whole town. The fuel filters and their spares were soon full of wax and the race was on to get the vehicle running again. From a mechanic selection point of view this was perfect. Rather than coming up with challenges and scenarios to put the candidates under pressure, mother nature was doing it all for us.

A cunning plan was devised. Andy Thomas, the Finning Project Engineer, would go with Craig Lusada, one of the candidates and Anton, to the nearest dealership to get some additional spare filters. This was a four hour drive. To be there when they opened the next morning would mean leaving at 04:00 hrs. The remaining four candidates would work in pairs in shifts on the CAT. They devised a whole separate fuel supply through which local fuel was fed. This by-passed the first fuel filter and water separator and would keep the engine running. Slowly but surely the engine would feed warm surplus fuel through to the existing tank and melt the waxed fuel which could then be used. More local fuel was added directly to the tank to help prevent further waxing.

During the night, the shift pattern was not strictly adhered to – the intentions were good but the need to stick to plans put in place for safety and the fact that this should be treated as a marathon and not a sprint had its consequences. In the morning the mechanics were assembled for a little group punishment – win together – lose together. We also made sure that everyone was there to witness it. They were asked to run a lap of the test track, not so easy in polar clothing and boots rated at -70C. The last one back would do it again. The actual purpose of this was not punishment at all, just an opportunity to see how they responded to the situation when they were cold, tired and as far as they were concerned had just performed miracles. They all did it. With what spirit they did it was as telling as we expected it to be.

The temperature had now settled at about -43C. It is hard to explain how this level of cold feels, it is more a presence that dominates almost everything you do – you can function but it takes more planning and consideration to do the simplest things. -43C is getting into the warmer end of what ‘The Coldest Journey’ will experience but was certainly good enough for our purposes. At lunchtime Andy Thomas, Craig and Anton returned triumphant with some of the most expensive Caterpillar spares known to mankind.

The team now split to carry out different tasks. One group would concentrate on getting sponsor photographs. The clear blue skies and snow drenched backdrop were ideal for this. In front of the camera would be Ran and Mike. Duty photographer was our co-expedition leader Anton Bowring. Supporting Anton and feeding through the sponsor patches was Tomo. In essence this is a simple procedure – the clothing had specific velcro sections to help quickly change the patches. In these temperatures however everything just gets harder and slower. Anton’s camera was getting temperamental and needed him to manually adjust and coax it on regular intervals.

In the local garage we asked what the bold headline was on the newspaper. ‘Sweden Paralysed’ came be back the answer. Not just us having fun then.

The bulk of the team were wearing clothing tested in the cold chamber and this was the first extended field trial. The feedback was positive with just a few issues on fitting over the boots for some people. Although our temperatures were now properly cold it is worth noting that we were in a very still, calm bowl with no wind to contend with during our entire stay. In Antarctica this wind will add a whole other level of complexity for the simplest of operations.

The CAT was now equipped and ready for its extended fuel burn testing and trundled around the test track giving all of our candidate mechanics some good driving time. Those not driving found plenty to do keeping the rest of the vehicle fleet operational. The vehicles were now left running 24 hours a day. From one of the vans Andy Thomas produced a cartridge of the neat additive that was to prevent the fuel from waxing – it was frozen solid.

From Antarctica the team will transmit data and video through the Iridium Openport satellite system. We took this system to Sweden, powered from one of the vehicles and connected to a laptop we transmitted a 2 minute video package back to the BBC in London. The data rate on Openport is quite slow which gives you time to ponder the circumstances that lead to standing around in -43C, by a frozen lake in Sweden, using a satellite network to talk to the BBC. On the expedition itself the cables to the Openport will be heavily insulated and protected. Here in the open, at this temperature, they were prone to snap under their own weight.

Anton’s account of ‘the case of the amazing fingers’:

I first noticed I had a problem when my fingers stopped hurting. It was bitterly cold and my camera controls were freezing up. My nose was streaming which resulted in an icicle, like a stalactite, hanging from my nostrils. A corresponding stalagmite had taken up position on the shutter release which caused it to jam solid. I was wearing two pairs of gloves rather than mitts in order to adjust the controls but it was clear that I would have to take off one pair to keep up with the photographic demands. It wasn’t long before my fingers had gone completely white and solidified like stone. Luckily I wasn’t short of experience around me. Mike Stroud was very experienced in dealing with the effects of frostbite and Ran’s missing fingers were testament to the likely outcome if action wasn’t taken immediately. For three hours I squirmed in great discomfort with my fingers in lukewarm water as they slowly thawed and blistered. It held us all in horrified fascination. Tomo dressed the wounds and lent me his hands when I needed help. A salutary lesson was learned in temperatures which were mild compared to those the team could expect in Antarctica. It took three months for my fingers to reach anything like normality. For that entire period, the little finger on my right hand (which hadn’t been affected) was working overtime to perform tasks normally shared with its colleagues. To this day, it remains exhausted!

Despite the slow start, we were now achieving many of our aims for Sweden. The sponsor photography and filming for the BBC and Caterpillar had taken longer than anticipated but the atmosphere was good and the cold had brought out the best in everyone.

One last push and we would be done. What could possibly go wrong?

Part 4 - The Pond of Doom

We had been in Arjeplog for the best part of week now, all 15 of us crammed into Farholm, our small rented house. Excellent, fortifying food was provided in hot containers at the house and on the test track by Karen Ingerbritsen and her team from the Simloc Hotel. They, like all the locals we met, had such a positive and refreshing ‘can do’ attitude, obviously fostered by their remoteness and the long winters.

Of our remaining tests, the most dynamic promised to be the crevasse crossing. Back in October, before the snow came, the GKN team had arranged for a series of trenches to be dug to our specification. These then filled with snow. We had four of them in a long run next to the main test track. The first was a metre wide ‘warm up’. The next was significantly wider but should not present any major issues. The third comprised two, metre wide trenches set only a metre apart so that the vehicle would still be dealing with the first when it encountered the second. The last trench was set be at the CAT’s limit such that it would need to use its front blade and get assistance from the mass of the caboose behind.

The crevasse crossing provided an opportunity to introduce the ‘Eagle’ Close Combat radios. Manufactured by Cobham, these came with the ability to create connected groups and a voice activation option. Matt Stevely the driver was connected with Spence, Steve and Andy Thomas who were marshalling and spotting. With this system we were able to calmly chat through commands and provide information despite the noise of the hard working CAT and trailer. An artfully positioned Go Pro camera was able to capture some great shots despite coming within a hairs breadth of the tow hitch of the CAT as it climbed out of one the crevasses.

In Antarctica there will be a lot of preventative vehicle maintenance and servicing. To create a safe microclimate in which to perform this work, each vehicle will have a roof mounted canopy. In Sweden was the first time this had been fitted to the vehicle and we wanted to run an overnight test.

Deployment worked well and the heat given off by the vehicle soon warmed the canopy. Geoff Long used his thermocouples and data logger from Portsmouth University to record the temperatures. The data showed that whilst it was -35C outside, inside it was +10C. This turned out to be one of the most successful tests of our stay in Sweden, with a very gradual heat drop off just needing a short boost from running the engine every few hours. The Webasto heating package that will be fitted to the vehicles in Antarctica should be able to provide such top ups on its own.

With the test programme complete it was just a matter of getting the CAT back over the hill, its blade off and loaded onto the truck using our bespoke ramp. It happened to be Spence who was the driver for this section. The candidate mechanics were also told that the formal selection activities were now concluded and it was just about getting home. The first run up the hill showed that the snow on sand combination was more of challenge than we thought. A few runs later and it slowly dawned that we could have an issue on our hands. Spence was getting higher each time but the last lip was beyond the available traction. A discussion was held and we agreed that we would see if there was a less steep, but longer route back that didn’t mean wiping out any trees. Such a route presented itself and we got ready – it wouldn’t be long until it got dark.

The CAT D6N has a winch cable which had to be found and released from under the water. The route back out had no anchor points within range, so a large earthmover was used. It cleared a path and then dug in its blade. The ground was just sand which was not the most secure anchor.

After clearing away as much snow and ice as we could from the rear of the CAT, the winch cable was locked around the blade of the earthmover. All spectators were moved well well back – a winch cable under tension is potentially lethal. The winch was engaged a lot of straining could be heard. Then the cable snapped. We were asking a lot of the cable and winch as the CAT has a system by which you can drive to the tracks or the winch but not both. This meant we could not assist the winch in any way.

Thankfully, where the cable had snapped, it still left a good working amount. The earthmover was moved forward and dug in. We did all we could to ease the angle at the water’s edge and we tried again. In the dark with lights blazing, exhaust fumes (and steam) coming from the vehicle, with the noise of the engine’s revving and of metal stretching it all seemed surreal. Then the cable snapped again. There was now not enough working length left.

It was at this point that the guys from the Colmis facility said that they would need to call in ‘The Beast’. It would take a couple of hours to get here. The Beast was a heavy weight recovery truck that is used in Northern Sweden to pull trucks back onto the road when they have gone off into snow drifts or the forest.

Late that night ‘The Beast’ arrived. It didn’t bother with winch cables but had extremely large chains. This would be easy we all thought. Then one of the chains snapped. It was at this point that we were seriously beginning to think that we would be back in the Spring to get the CAT from the water. Some people started mapping out alternative career paths.

Multiple chains were then used and with a flourish the CAT was out. It looked a mess but was still functioning – and it was still on the wrong side of the hill. With the temperature having dropped further during the night we thought it might be worth having another go at Plan A. This would now be a more solid surface than earlier in the day. It was determined that the most experience operator from all those present was Brian from the Perkins team. One might assume that we would have pushed for one of the expedition team to do it, but this was all about getting the job done and safely.

Brian did the business but was the first to admit that it had been borderline. That was enough for today.

Back at the house we had the last of our selection team daily meetings in the basement to discuss the progress and performance of our candidates. Although the ‘Pond of Doom’ had happened after we had formally ended the selection, we could not ignore any lessons learnt. Having such an event occur when people think they are finished can give a real insight to personalities.

The following morning, while the mechanics removed the CAT’s blade, cleaned the CAT and loaded it onto the transport, we spoke to the BBC crew and the Caterpillar PR team. They too had spent a week with our candidates and we wanted their opinions. Their comments were informative and much to our surprise their conclusions were the same as ours. We then bid them goodbye as they escaped to civilisation.

The rest of the expedition equipment was packed and the house cleaned as best we could with the gear in the way. We would be leaving the next morning. That night was quiet one with a DVD on the projector.

Early the next morning the minibus went North through what had become very murky, blowy weather to get to the marker for the Arctic circle. Those who stayed at the house finished the cleaning and loaded Anton’s van.

Team photos at the Arctic Circle and getting the souvenir shop to open early. Back to Arjeplog, load up and head home. The journey back was to be split with an overnight stay on the outskirts of Stockholm. As we headed South however, it was becoming clear that our progress in this weather was not going to let this happen. With some regret we rang the hotel and consigned ourselves to what turned out to be a 29 hour drive.

Back in Esbjerg there was just enough time for Anton to have a trip into A&E at the local hospital. His blisters were now bursting and even though he would never show it, he was in much pain. With his hands dressed and placed in bags with antibiotic cream, he had a long ferry ride to look forward to. Early evening we made it onto the ferry. No lessons or presentations – just the bar to be entertained by a Johnny Cash/Elvis tribute act.

Next morning, with a grey sea out of the windows and variable amounts of sleep, Ran and Steve had the never welcome task of telling the candidates how they had done. Everyone had put in a huge effort so diplomacy and tact were called for. As is usual it was Steve who had to deliver the bad news. Our successful candidates were Spence and Danny.

Back in Harwich most of us kept well out the way while Ran handed Anton back to the care of his family. “I wonder if she will let him out to play with Ran again?” someone quipped.

The British roads seemed so busy and Cannock couldn’t come quick enough. Eventually we made it back, unloaded and then headed our separate ways. Our Swedish Saga was now over.

At home Steve was met with the comment “It got really cold while you were away – we had minus ten one day.”